In the world of winemaking, the delicate balance of glucose and fructose management is key to achieving that perfect bottle of wine. These sugars aren’t just part of the natural grape composition – they’re the backbone of the wine flavor, sweetness, and overall quality. Whether you’re crafting a dry red or a delicate white, understanding and frequently measuring these sugars throughout the winemaking process is crucial for consistent fermentation and quality finished product.

The Role of Glucose and Fructose in Wine and It’s Frequent Measurement

During ripening, grapes undergo significant changes, one of the most critical being the accumulation of the monosaccharide sugars glucose and fructose. Initially before veraison, these sugars are nearly undetectable (Waterhouse et al., 2016). However by harvest, their combined concentration can reach between 180-250 g/kg (Waterhouse et al., 2016). After water, these sugars are the most abundant substances in grapes and pivotal in assessing grape composition and ripeness.

Glucose and fructose sugars serve as the primary substrate for yeast to produce ethanol during alcoholic fermentationand contribute to perceived sweetness of the final product. As yeast is glucophilic (they consume glucose more readily), the concentration of fructose is typically higher than glucose at the end of fermentation (Berthels, 2004).

Fructose is almost twice as sweet as glucose, making its presence particularly significant in influencing the sweetness and overall sensory profile of the wine (Moreno & Peinado, 2012).

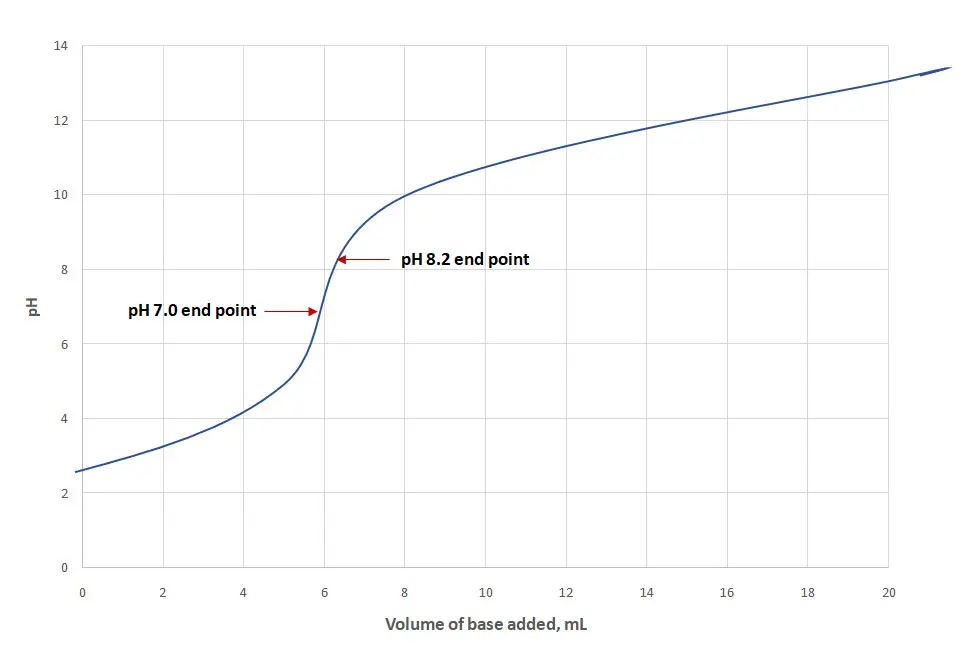

Figure 1: The relationship between live yeast cells, sugar and ethanol concentrations.

The sweet taste of sugars in wine not only enhances the perception of body, but also interacts with other taste and tactile sensations. For instance, sweetness can influence sourness, bitterness, astringency, and pungency, creating a more balanced and pleasant taste experience.

Why do we measure glucose and fructose?

Measuring glucose and fructose in wine is essential for several reasons, all of which contribute to the quality, consistency, and regulatory compliance of the final product. These measurements are crucial for winemakers to achieve desired outcomes in terms of sweetness, fermentation efficiency, and adherence to industry standards.

Perceived sweetness

Fructose is inherently sweeter than glucose, which directly impacts the wine sweetness and overall flavor profile. Higher levels of fructose can make the wine taste sweeter even if the total sugar content remains constant (Berthels, 2004). Understanding the ratio of these sugars allows winemakers to predict and control the perceived sweetness of the wine. This is particularly important for:

“Measurement is the first step that leads to control and eventually to improvement.”

H. James Harrington

- Flavor profile: Ensuring the desired balance of sweetness, which enhances the appeal to target consumers.

- Product differentiation: Creating distinct wine styles ranging from dry to sweet based on the sugar profile (Grainger & Tattersall, 2016).

Balance and rate of fermentation

The concentration of glucose and fructose can significantly influence the fermentation process. A balanced ratio of these sugars is ideal for smooth and efficient fermentation. An imbalance can lead to several issues:

- Sluggish fermentation: Occurs when yeast activity slows down due to an unfavorable sugar ratio, potentially leading to incomplete fermentation (Berthels, 2004).

- Stuck fermentation: When fermentation stops prematurely, leaving residual sugars, sometimes leading to wine spoilage, sweeter than desired taste and quality downgrades (Berthels, 2004).

Compliance and labeling

At the time of publishing this article, accurate measurement of glucose and fructose is required for European labelling compliance and consumer information (Wine Australia, 2024). Providing precise information about sugar content on wine labels helps European consumers make informed purchase decisions.

How often and when should we conduct glucose and fructose measurements?

Conducting glucose and fructose measurements at key stages of the winemaking process is crucial for monitoring and ensuring the quality of the wine. Here is a breakdown of the critical times to measure these sugars and the recommended frequency of testing.

Key stages for measuring glucose and fructose

- Pre-harvest (grape ripeness assessment), using refractometry.

- Timing: Start a few weeks before the anticipated harvest date.

- Frequency: Weekly or bi-weekly.

- Purpose: To better determine the optimal harvest time based on sugar accumulation in the grapes (Zoecklein & Gump, 2022). This helps to ensure the grapes are picked at peak ripeness, which is crucial for achieving the desired sugar levels and flavor profile in the wine.

Figure 2: Refractometers are used to measure grape juice brix (dissolved solids) which is correlated to sugar content. (Image from www.walmart.com)

- At harvest, using refractometry.

- Timing: On the day of harvest.

- Frequency: Once.

- Purpose: To confirm the sugar levels in the grapes at the time of harvest.This provides a baseline measurement for the winemaking process.

- During fermentation

- Timing: Throughout the fermentation process.

- Frequency: Daily or every two days, depending on the fermentation speed and style of wine being produced.

- Purpose: To monitor the progress of fermentation, ensuring that the yeast is converting sugars to alcohol effectively. Frequent measurements help detect any issues such as sluggish or stuck fermentation early, allowing for timely interventions.

- Post-fermentation

- Timing: Immediately after fermentation is complete.

- Frequency: Once.

- Purpose: To verify that the fermentation process has been completed and to measure the residual sugar levels in the wine. This is particularly important for determining if the wine meets the desired sweetness level and for classifying the wine (e.g., dry, semi-sweet, sweet).

- Before bottling

- Timing: Prior to bottling the wine.

- Frequency: Once.

- Purpose: To ensure that the residual sugar levels are stable and meet the desired specifications (Crowe, 2017). This final check is critical for quality control, ensuring the wine is ready for the market.

Additional considerations

- Sluggish or stuck fermentation: If any signs of sluggish or stuck fermentation are detected (e.g., slower-than-expected reduction in sugar levels), more frequent measurements are necessary to monitor and address the issue.

- Quality Control: For higher quality and premium wines, more frequent measurements throughout the entire winemaking process may be justified to ensure precision and consistency.

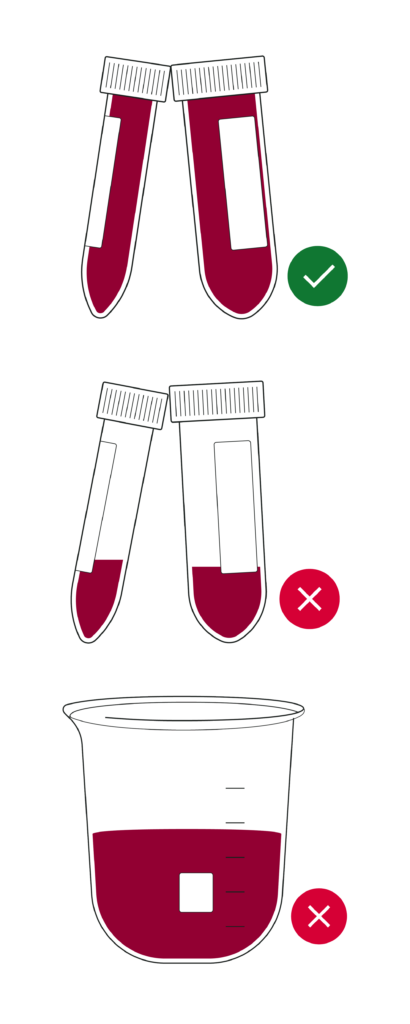

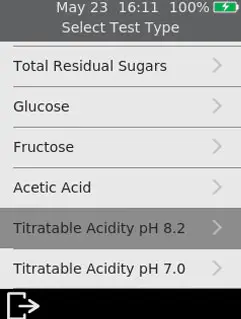

Regular and strategic monitoring of glucose and fructose at key stages of winemakingis essential for ensuring optimal fermentation, achieving desired sweetness levelsand maintaining product quality. Sentia measures glucose and fructose separately, detecting levels from 0.1 to 10 g/L for each sugar, making it an ideal tool for end-of-fermentation analysis in both dry and semi-dry wine styles.Want to see Sentia in action? Contact us today, and a team member will reach out to you to discuss how it can enhance your winemaking process!

What do you think? Contact us here and tell us about your sugars monitoring during fermentation. Did you find this article useful?

References

Berthels, N., Cordero Otero, R., Bauer, F., Thevelein, J., & Pretorius, I. (2004). Discrepancy in glucose and fructose utilisation during fermentation by Saccharomyces cerevisiae wine yeast strains. FEMS Yeast Research, 4(7), 683–689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.femsyr.2004.02.005

Crowe, A. (2017). Checklist: Getting Your Wine Ready for Bottling Day. Wine Business Monthly.

Grainger, K., & Tattersall, H. (2016). Wine Production and Quality (2nd Ed.). John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Moreno, J., & Peinado, R. (2012). Enological Chemistry. Elsevier Science & Technology.

Waterhouse, A., Sacks, G., & Jeffry, D. (2016). Understanding Wine Chemistry.John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Wine Australia. (2024). Compulsory energy, nutrition and ingredient labelling in the European Union from December 2023.Australian Government, Wine Australia.

Zoecklein, B & Gump, B. (2022).Practical methods of evaluating grape quality and quality potential. In Managing Wine Quality. Vol. 1, Viticulture and Wine Quality (2ndEd.). Woodhead Publishing.